Access to this page has been denied a human (and not a bot).Press & HoldPlease check your network connection or disable your ad-blocker.’; document.body.appendChild(div); }; ]]>

Continue reading

Author: jeff

The 57th Algonquian Conference, an international gathering of Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars, students, cultural workers, language practitioners, artists, and community members, will take place October 17-19 at The University of Winnipeg. Registration is now open and a list of key dates is available online.

Up to 200 attendees are expected from across Canada, the United States, and beyond. In-person and online presentations are planned, plus roundtables, workshops, panels, a keynote address, and a special variety show evening.

The Algonquian Conference is an annual interdisciplinary forum for research on topics related to Algonquian peoples, said Heather Souter, a Michif (Métis) faculty member in the Department of Anthropology and Indigenous Languages program and member of the conference’s organizing committee.

Canada and the U.S. take turns hosting the annual conference. Last year’s gathering took place in Oklahoma City. UWinnipeg is pleased to host this year’s conference. For the first time, the majority of the conference’s organizing committee is Indigenous.

“The committee has been working hard to ensure all participants can engage with each other in ways that help them see beyond stereotypes, trauma, and superficial differences to our shared humanity and a shared and hopeful future,” Souter said.

“We aim to help foster relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars and community members based on mutual respect and reciprocity while promoting recognition of each Indigenous nation’s sovereignty and autonomy, particularly in the context of knowledge and research.”

The Algonquian family of languages includes Cree, Anishinaabemowin, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Mi’kmaq, Arapaho, and Fox-Sauk-Kickapoo, and others. Both Southern and Northern Michif are rooted in this language family as well.

“Algonquian peoples represent the largest combined group of First Peoples in Canada,” Souter said. “They are found from the East Coast of what is now known as Canada and the United States, to as far…

Soccer Recap: Wilkes-Barre Victorious

After low-scoring totals in their previous four matchup, Wilkes-Barre brought some dynamite into their most recent contest. Their defense stepped up to hand the Greater Nanticoke Area Trojans a 4-0 shutout on Friday. Wilkes-Barre have beaten Greater Nanticoke Area the last five times they’ve met, but they better watch out: this was the closest Greater Nanticoke Area has come to flipping the script.

vs

| 09/05/25 – Home | 4-0 W |

| 09/28/24 – Home | 1-0 W |

| 09/06/24 – Away | 3-1 W |

| 10/15/19 – Neutral | 4-1 W |

| 09/23/19 – Away | 3-1 W |

Wilkes-Barre now has a winning record of 3-2-1. As for Greater Nanticoke Area, their defeat dropped their record down to 1-4-2.

Wilkes-Barre didn’t take long to hit the pitch again: they’ve already played their next game, a 4-2 loss against Wyoming Valley West on the 9th. Greater Nanticoke Area has also already played their next matchup (against Dallas), but no score has been uploaded at the time of writing.

Article generated by infoSentience based on data entered on MaxPreps

Suggested Video

Access to this page has been denied

Access to this page has been denied a human (and not a bot).Press & HoldPlease check your network connection or disable your ad-blocker.’; document.body.appendChild(div); }; ]]>

Continue reading

Councillor Metcalfe speaks on swing MZO vote | The Haldimand Press

Saturday, September 13, 2025

Locally owned, community driven. Since 1868.

6 Parkview Rd. Hagersville, ON, N0A 1H0

Get notified when the latest news is posted.

The Haldimand Press © Copyright 2018 – 2025, All Rights Reserved

Get notified when the latest news is posted.

The feature of the final Sunday night card of 2025 at Pocono Downs at Mohegan Pennsylvania was a $15,753 fast-class conditioned trot, in which the Kadabra-P L Glitter mare P L Notsonice had a not-so-nice trip, but still won in 1:54.

Anthony Napolitano tucked in third early with P L Notsonice in a :27.1 quarter put up by One After Nine (Jim Pantaleano), then considered quarter-moving but was beaten to that tactic by Cassius Hanover (Kevin Wallis), who gained the top and slowed to the half in :57. P L Notsonice was out again on the grind through three-quarters in 1:25.3 and for the rest of the way, and the favoured mare’s class came through as she battled to the front and beat longshot One After Nine by a neck, with Cassius Hanover third. P L Notsonice is now a 41-time winner in 160 lifetime outings with $831,716 in earnings. Anthony Faulkner trained her to victory for Elite Harness Racing LLC. The eight-year-old mare paid $3.60.

There were two impressive two-year-old winners on the card. The first was the Stay Hungry-The Santafeexpress filly Santafes Hungry ($13.60), who was just along to catch heavy favourite Amira Hanover (Braxten Boyd) and break her maiden in 1:53.4, racing her back fractions in :55.4 and :27.3 for driver Matt Kakaley, trainer Carl Conte Jr., and owner Ed De Rosa. The other was the Greenshoe-Ma Was Right gelding Credible Control ($9), who came up the inside after a blistering pace to win for the first time in 1:57.2 for the meet’s leading driver and trainer, Tyler Buter and Ron Burke, and the partnership of Burke Racing Stable LLC, Larry Karr, Knox Services Inc., and Beasty LLC.

Driving doubles were posted by Kakaley and amateur Tony Beltrami.

Pocono now switches to a basic schedule…

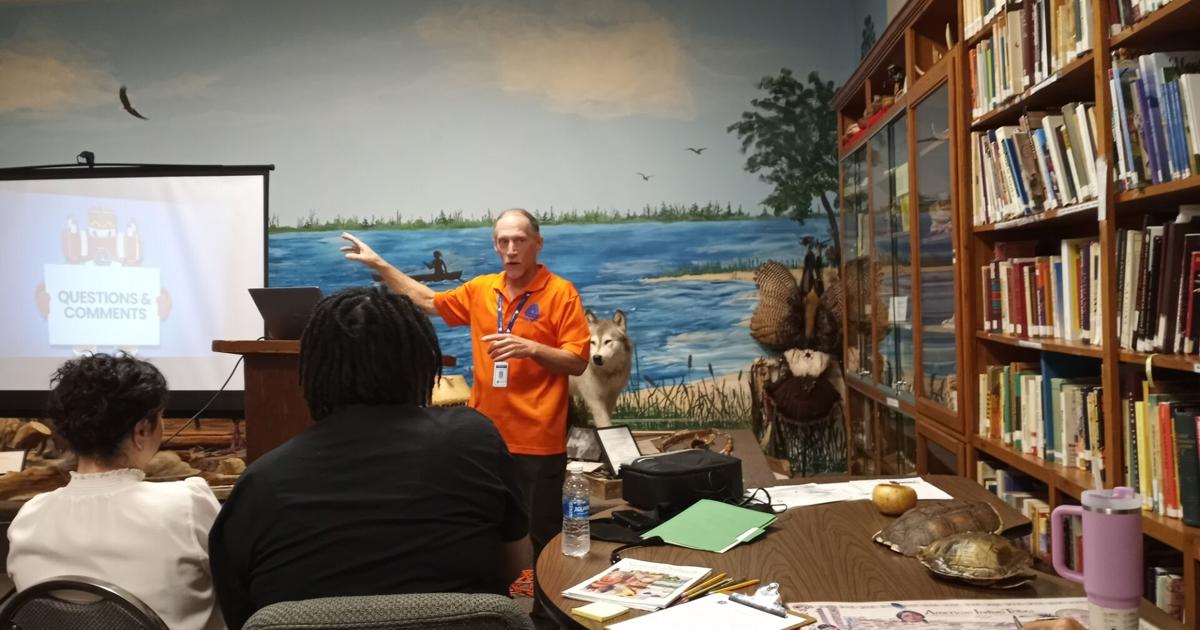

Archaeological digging for the north Millsboro bypass turned up some pottery pieces, but no human remains or very significant finds during the years of study, design and construction. Delaware Department of Transportation (DelDOT) archaeologists dug into the topic at an Aug. 21 lecture at the Nanticoke Indian Museum.

Throughout humanity, people followed animal trails, which were widened to become paths, then widened again and again to accommodate horses, carts, cars, trucks and modern traffic. In 1917, Delaware created a central highways department as roads were dug by hand and then by machine. By the middle of the 20th century, more research went into materials, traffic and design.

Finally, the U.S. started paying attention to what was being paved over.

“One of the things that came in the 1960s was the idea of preservation,” said Micaela Younger, a DelDOT architectural historian. She pointed to Williams Pond in Seaford as an example of the before-times. It was dammed up in the 1950s or ’60s, without any cultural studies beforehand.

“Was there an environmental damage? We do not know. Was there any cultural significance? We don’t know. Did they find anything? We don’t know. So, with that, came this whole movement to kind of preserve public opinions.”

By 1970, Congress created the National Historic Preservation Act and the National Environmental Policy Act. That legislation created requirements for researching and asking the general public how projects might impact the local landscape, culture, history and ecology.

“When there is any federal involvement … the federal agency is responsible for taking into consideration the effect of the projects on the historic resources and providing a chance for there to be comment,” said archaeologist John Martin, DelDOT’s Cultural Resources Program supervisor.

A dropped pot or a potential trove?

Set to open on Sept. 22, the new bypass will wrap around the northeast side of Millsboro,…

Winnipeg, MB — The University of Winnipeg will host the 57th Algonquian Conference this fall, bringing together scholars, students, cultural workers, and community members from across North America to share research and celebrate the diversity of Algonquian languages and cultures.

Scheduled for October 17–19, the event is expected to draw up to 200 participants from Canada, the United States, and beyond. Organizers say the gathering will feature both in-person and online presentations, along with workshops, roundtables, panels, and a special cabaret-style evening showcasing Indigenous performance and language.

A Gathering of Shared Knowledge

The Algonquian Conference has long served as an international forum for interdisciplinary research related to Algonquian peoples. While Canada and the U.S. alternate hosting duties each year, this marks the first time the University of Winnipeg has welcomed the event.

Heather Souter, a Michif (Métis) faculty member in the Department of Anthropology and Indigenous Languages program and a member of the conference’s organizing committee, emphasized the significance of this year’s meeting.

“The committee has been working hard to ensure all participants can engage with each other in ways that help them see beyond stereotypes, trauma, and superficial differences to our shared humanity and a shared and hopeful future,” Souter said.

She added that the conference aims to strengthen relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars while underscoring “recognition of each Indigenous nation’s sovereignty and autonomy, particularly in the context of knowledge and research.”

The Role of Algonquian Languages

The Algonquian language family is among the largest in North America, spanning communities from the Atlantic coast to British Columbia and south into Oklahoma. It includes Cree, Anishinaabemowin, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Mi’kmaq, Arapaho, Fox-Sauk-Kickapoo, and both Southern and Northern Michif.

“Algonquian peoples represent the largest combined group of First Peoples in Canada,” Souter noted.

This linguistic and cultural diversity will be front and…

Learn About First People in Our Area

The Lenape people are Indigenous to the Delaware Valley, and unless you are descended from the Lenape or other Native American tribes, you are not Indigenous. From parts of New York and eastern Pennsylvania to New Jersey and the coast of Delaware, the Lenape lived in this region for thousands of years.

They were the first inhabitants of the lands now known as Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where many of the county parks, historic sites, nature centers and place names acknowledge the Lenape’s role as the original caretakers of this land through exhibits and signage.

To learn more about the Lenape and their culture, join Jennie Dancing Butterfly, cultural historian and member of the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania, Native Americans of the Northeastern Woodlands, as she discusses Lenape culture and language from 6:30 to 8 p.m. Sept. 25 at the Schuylkill County Historical Society, 305 N. Centre St., Pottsville.

Jennie Dancing Butterfly is a Lenape woman who grew up in Berks County. Both of her parents were members of Turtle Island Chautauqua in Lancaster County and participated in the teachings of Doris Riverbird and Chief Carl White Eagle. She incorporates her parents’ knowledge with experience from her own life’s journey, while learning about her culture and heritage.

She will provide a display of her parents’ regalia, as well as her own, and will also talk about the Lenape language (Unami dialect) and being part of revitalization efforts. A certified instructor, she has been studying the language for four years. The program will be highlighted by traditional Lenape stories.

This event is free for historical society members and $5 for nonmembers.

In addition, the society is looking for volunteers to help in the gift shop, scan photos, set up displays, assist with events, record programs, and do whatever it takes to preserve…

Please restore Nober Park so the grass can be mowed

To the Editor,

I am expressing my anger for the way Haldimand County destroyed an area once beautiful with mowed lawn and flower beds.

The road property is located at County Line 74 and the Thompson Road, which goes west into Waterford.

A few years ago, Haldimand County repaved part of County Line 74. Ditches were also cleaned, and truckloads of dirt and debris were dumped on this road property. The plan was that the lower area of this property would be filled in, but only to the top of the two long flower beds. The two flower beds should have remained untouched, and the dirt dumped to fill the low area should have been leveled and seeded. That did not happen.

The truck loads of roadside dirt covered the entire area, destroying the two flower beds. The ground was never leveled down to allow the grass to be mowed.

Weeds have now taken over.

I live nearby and maintained this property for many years at no cost to anyone. The Waterford and District Horticulture Society and I created the flower beds and planted flowers in them starting in 1982. Some called the property the Nober Park.

I complained when all the destruction took place. Instead of levelling the ground, a truck was brought in and grass seed was spread over the mess to try and cover it up.

Will Haldimand County please fix the damage they caused, by first leveling and removing any rocks or other debris put there? Once this is fixed, grass can be seeded and mowed to beautify the countryside.

How would you feel if someone dumped truckloads of dirt and…