R | 1h 52min | Action, Adventure, Drama | 1992

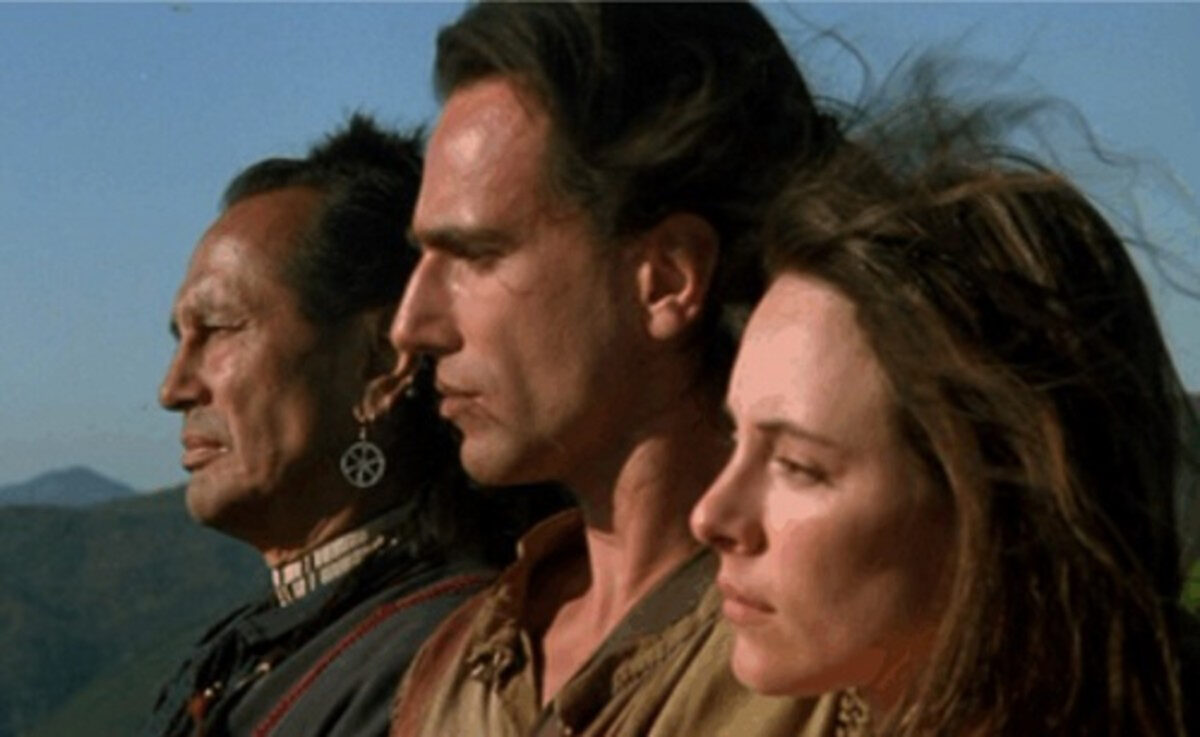

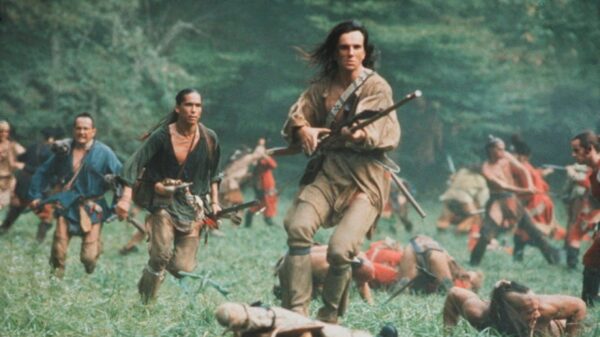

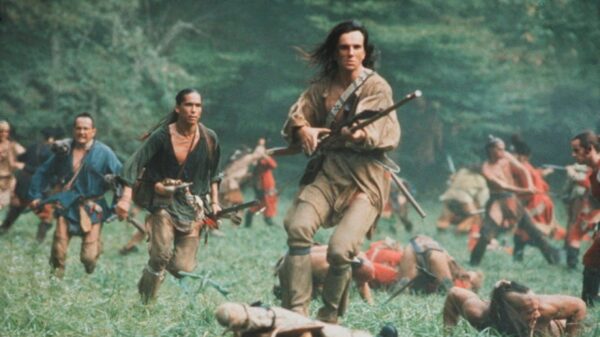

Hawkeye (Daniel Day-Lewis) leads an attack, in “The Last of the Mohicans.” (20th Century Fox)

Hawkeye (Daniel Day-Lewis) leads an attack, in “The Last of the Mohicans.” (20th Century Fox)

Filmmakers who attempt to make historical dramas have to walk a careful tightrope when attempting to appeal to a mass audience. On one hand, if they focus on too much historical accuracy, the action can become bogged down to the extent that you feel like you’re watching a rather dry documentary. And, on the other hand, if they play a little too fast and lose with historical accuracy, their projects won’t be taken seriously.

Based on an 1826 novel by James Fennimore Cooper and directed by Michael Mann, 1992’s “The Last of the Mohicans” not only successfully traverses the aforementioned tightrope, it does so with self-confident assurance.

This is a bold, visionary film the likes of which one sees only once in a while. Although Cooper’s book has been adapted on the big screen numerous times, this version has the most historically accurate feel to it, and features some gorgeous outdoor photography and a highly memorable score to boot.

The film is set in 1757, during the onset of the French and Indian War (1754–1763). The British and French are viciously vying for control of eastern North America and both countries utilize Native Americans to bolster their armies. While the Mohican tribe is allied with the British, the Hurons side with the French.

Hawkeye (Daniel Day-Lewis, L) showing why he’s so named to adoptive brother Uncas (Eric Schweig), in “The Last of the Mohicans.” (20th Century Fox)

Hawkeye (Daniel Day-Lewis, L) showing why he’s so named to adoptive brother Uncas (Eric Schweig), in “The Last of the Mohicans.” (20th Century Fox)

The film opens up…