The Berkshire Museum’s repatriation of remains to the Stockbridge-Munsee tribe was part of a larger process that began in 1990 when a landmark federal law ordered America’s museums and universities to return Native American cultural objects.

When the Berkshire Museum gives two sets of human remains to the Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians, it will be a successful step forward for a process as difficult as it is morally necessary. It will not only be a clear-eyed accounting of a deep historical wound but an example of how, with respect and recognition, it is never too late to hope for healing and reconciliation.

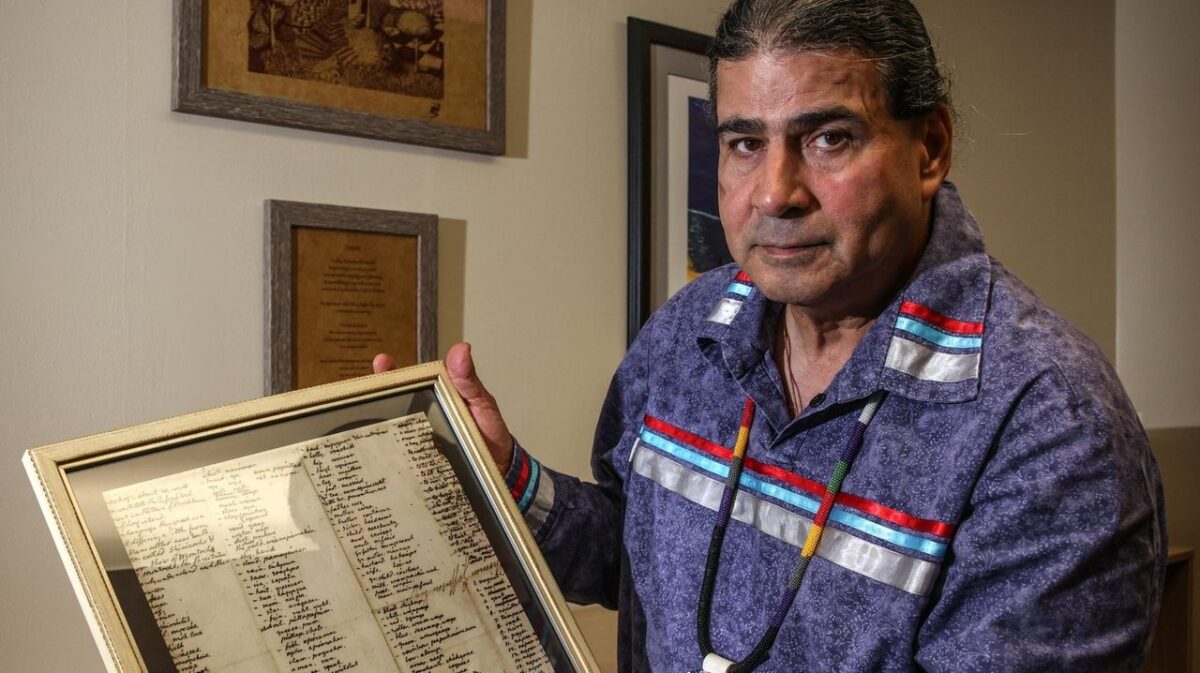

The remains are set to be transferred from the custody of the Berkshire Museum to the Stockbridge-Munsee tribe, which plans to give them a dignified reburial. The remains were donated to the Berkshire Athenaeum in 1932. Years before that, in the late 19th century, they were recovered in a river washout in the late 19th century in the area of Springfield and Longmeadow. Like so many Native American remains once laid to rest in tribal burial locations, they were carelessly unearthed by the same forces of expanding American empire that pushed their peoples out, catalogued and stored as exhibits and artifacts without regard for the wishes or traditions of the deceased individuals or their tribes.

How would you feel if your family’s bones were raked from the earth and appropriated as the property of those whose ancestors dispossessed yours? Unfortunately, many Native Americans don’t have to imagine such a rending ordeal adding insult to the injury of displacement and destruction.

Fortunately, much has changed in the world of museum ethics…

John White’s watercolor painting of a group of Carolina Algonquian fishing.

John White’s watercolor painting of a group of Carolina Algonquian fishing.